Tuesday

RIC

Nearly every weekday afternoon Matilda was left alone in the house. Her brother (five years older than her) went to school. Her father went to work and her mother went out playing bingo in a town eight miles away. Mrs Wormwood was hooked on bingo and played it five afternoons a week. On the afternoon of the day when her father had refused to buy her a book, Matilda set out all by herself to walk to the public library in the village. When she arrived, she introduced herself to the librarian, Mrs Phelps. She asked if she might sit awhile and read a book. Mrs Phelps, slightly taken aback at the arrival of such a tiny girl unaccompanied by an adult, nevertheless told her she was very welcome.

‘Where are the children’s books, please?’ Matilda asked.

‘They’re over there on those lower shelves,’ Mrs Phelps told her. ‘Would you like me to help you find a nice one with lots of pictures in it?’

‘No, thank you,’ Matilda said. ‘I’m sure I can manage.’

R: What do Matilda's parents do during the day?

I: How do you think Matilda felt when her father refused to buy her a book? Why?

C: What does the word unaccompanied mean?

Tuesday 10th December 2024

LC: To retrieve key facts – Roman food

Task: Read the information below and answer the questions.

What different types of food did the Romans eat?

What did the Romans drink?

What did the rich Romans eat?

What did the poor Romans/slaves eat?

The Romans ate a varied diet consisting of vegetables, meat and fish. The poorest Romans ate quite simple meals, but the rich were used to eating a wide range of dishes using produce from all over the Roman Empire.

Romans typically ate three meals a day – breakfast (ientaculum), lunch (prandium) and dinner (cena). Cena was the main meal.

The Romans did not sit down at a tables to eat their meals. They spread out on couches around a low, square table. They basically ate lying down! They also ate most of their meals with their fingers (although they did use spoons for some of the dishes, such as soup, and have knives to cut their food into bite-size pieces).

Fruit and Vegetables

A range of different fruits and vegetables were eaten by the Romans. They would have had: carrots, radishes, beans, dates, turnips, pears, plums, pomegranates, almonds, olives, figs, celery, apples, cabbages, pumpkins, grapes, mushrooms and many more. Some of these fruits and vegetables had never been seen in Britain before the Romans invaded.

Meat

The Romans kept animals for their meat. The rich ate beef, pork, wild boar, venison, hare, guinea fowl, pheasant, chicken, geese, peacock, duck, and even dormice (served with honey). The poorer Romans didn’t eat as much meat as the rich, but it still featured in their diet.

Fish

Lots of seafood was consumed by the Romans. They particularly enjoyed shellfish and fish sauce known as liquamen.

Bread and Porridge

Bread was a staple part of the Roman diet. Three grades of bread were made, and only rich ate refined white bread.

Pottage, a thick porridge-like stew, was made from millet or wheat. To this the Romans would add cooked meats, sauces and spices.

The Romans liked cheese (which was mainly made from goat’s milk) and eggs (from a variety of different birds).

Roman Banquets:

Romans didn’t know about sugar, so honey was used as a sweetener. Rich Romans also used salt, pepper and a range of spices to add flavour to their meals.

Wine was the main drink of the Roman Empire. It was always watered down and never drunk ‘straight’. In addition to drinking wine, the Romans also drank wine mixed with other ingredients. Calda was drunk in the winter and was made from wine, water and spices. Mulsum was a honey and wine mixture.

The Romans didn’t drink beer and rarely drank milk.

The daily Roman cuisine

For the ordinary Roman, their diet started with, ientaculum – breakfast, this was served at day break. A small lunch, prandium, was eaten at around 11am. The cena was the main meal of the day. They may have eaten a late supper called vesperna.

Richer citizens in time, freed from the rhythms of manual labour, ate a bigger cena from late afternoon, abandoning the final supper.

The cena could be a grand social affair lasting several hours. It would be eaten in the triclinium, the dining room, at low tables with couches on three sides. The fourth side was always left open to allow servants to serve the dishes.

Diners were seated to reflect their status. The triclinium would be richly decorated, it was a place to show off wealth and status. Some homes had a second smaller dining room for less important meals and family meals were taken in a plainer oikos.

The Roman diet

The Mediterranean diet is recognised today as one of the healthiest in the world. Much of the Roman diet, at least the privileged Roman diet, would be familiar to a modern Italian.

They ate meat, fish, vegetables, eggs, cheese, grains (also as bread) and legumes.

Meat included animals like dormice (an expensive delicacy), hare, snails and boar. Smaller birds like thrushes were eaten as well as chickens and pheasants. Beef was not popular with the Romans and any farmed meat was a luxury, game was much more common. Meat was usually boiled or fried – ovens were rare.

A type of clam called telline that is still popular in Italy today was a common part of a rich seafood mix that included oysters (often farmed), octopus and most sea fish.

The Romans grew beans, olives, peas, salads, onions, and brassicas (cabbage was considered particularly healthy, good for digestion and curing hangovers) for the table. Dried peas were a mainstay of poorer diets. As the empire expanded new fruits and vegetables were added to the menu. The Romans had no aubergines, peppers, courgettes, green beans, or tomatoes, staples of modern Italian cooking.

Fruit was also grown or harvested from wild trees and often preserved for out-of-season eating. Apples, pears, grapes, quince and pomegranate were common. Cherries, oranges, dates, lemons and oranges were exotic imports. Honey was the only sweetener.

Eggs seem to have been available to all classes, but larger goose eggs were a luxury.

Bread was made from spelt, corn (sometimes a state dole for citizens) or emmer. The lack of ovens meant it had to be made professionally, which may explain why the poor took their grains in porridges.

The Romans were cheese-making pioneers, producing both hard and soft cheeses. Soldiers’ rations included cheese and it was important enough for Emperor Diocletian (284 – 305 AD) to pass laws fixing its price. Pliny the Elder wrote on its medicinal properties.

Most of these were the foods of the wealthy. The poor and slaves are generally thought to have relied on a staple porridge. Bones analysed in 2013 revealed poor Romans ate large amounts of millet, now largely an animal feed. Barley or emmer (farro) was also used.

This porridge, or puls, would be livened up with what fruit, vegetables or meats that could be afforded.

Dining out was generally for the lower classes, and recent research in Pompeii has shown they did eat meat from restaurants, including giraffe.

Fish sauce

All classes had access to at least some of Rome’s key ingredients, garum, liquamen and allec, the fermented fish sauces.

The sauces were made from fish guts and small fish, which were salted and left in the sun. The resulting gunk was filtered. Garum was the best quality paste, what passed through the filters was liquamen. The sludge left at the bottom of the sieve was a third variety, allec, destined for the plates of slaves and the really poor.

Herbs would be added to local or even family recipes.

These highly nutritious sauces were used widely and garum production was a big business – Pompeii was a garum town. Soldiers drank it in solution. The poor poured it into their porridge. The rich used it in almost every recipe – it might be compared to Worcestershire sauce or soy sauce or far-eastern fish sauces today – from the savoury to the sweet.

Tuesday 10th December 2024

LC: To innovate a plan based on a plot pattern.

Using the story of Rumaysa and your innovated villain, plan your own story. Remember to include key skills you want to include in your story.

10.12.24

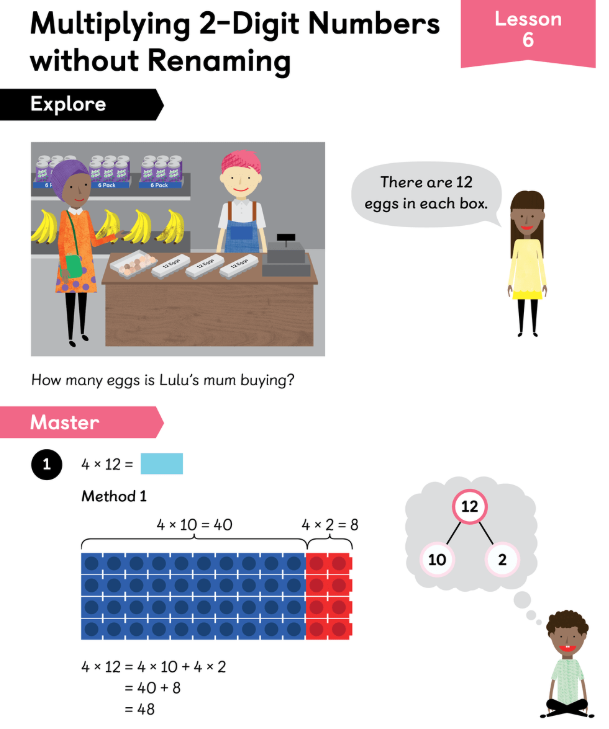

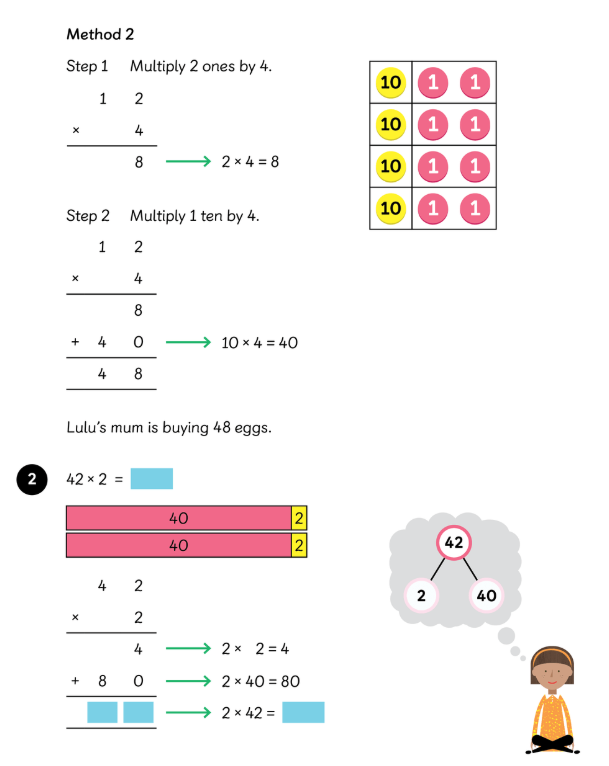

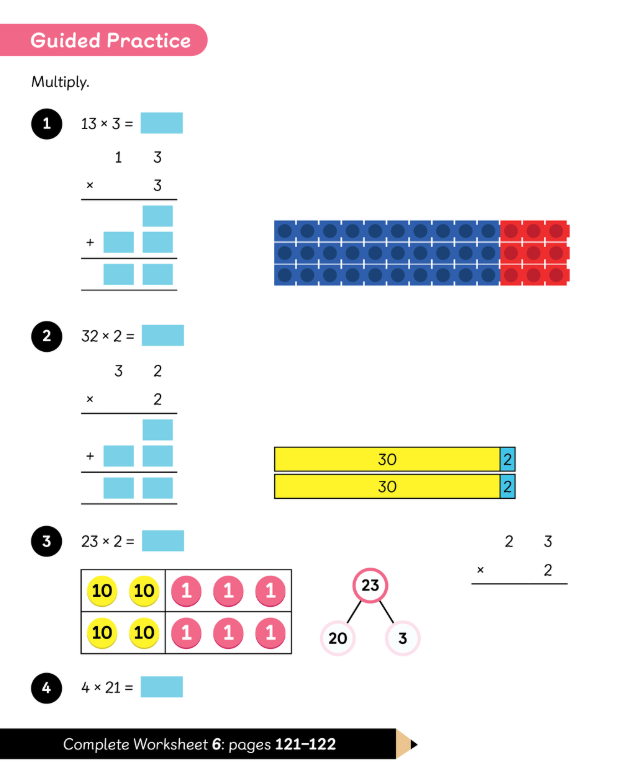

LC: To multiply a 2 digit number without renaming.

Tuesday 10th December 2024

LC: To reflect on the key messages from parables that could be passed on to others.

Which parables have we looked at?

What did they teach us?

Who might you recommend these parables to and why?

Fables and parables contain messages that have been passed on from generation to generation to guide people to live good lives.

Task: Identify one or two key messages that you would like to be pass on.

How could you teach others or pass on these messages to others?

LC: To encourage us to consider the importance of spreading positive news.

‘Who’s had some good news recently?’

How it make you feel when they hear someone else’s good news. Does it give you a buzz? Does it make feel you a bit jealous? Does it encourage you to feel optimistic?

- The Bible contains four good-news stories. They are the four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The word ‘gospel’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon language, one of the root languages of modern English. Gospel is literally ‘god-spell’ or ‘good story’.

There is a special day for remembering St Mark, the writer of Mark’s Gospel, which occurs every year on 25 April. We’re not entirely sure who Mark was, but he was interested in spreading good news. His symbol is the winged lion, which is also the symbol of the city of Venice. - For Mark, the best news that he’d ever heard was the story of Jesus. The story was world-shattering in its implications, and described a man who was also God; who lived a dramatic and influential life, turning upside-down the values of his community; who eventually died an unjust death, crucified on a Roman cross, but was brought back to life.

It is thought that Mark was the first one to write down the story of Jesus. His version is short and punchy, without many of the details contained in the other three Gospels. He just wanted to get the good news out. There was a problem, though: Mark wasn’t there for all of the events that happened in Jesus’ life. So, he turned to the next best thing: he interviewed the best eyewitnesses. - Simon Peter was regarded as Jesus’ right-hand man, chosen by Jesus himself. He was there from the beginning to the end of the significant final three years of Jesus’ life. So, Mark took the stories that Peter told and turned them into his good-news story. He even included all those times when Peter let Jesus down, misunderstood what he was doing or simply embarrassed himself. It’s a good-news story that rings true. And it doesn’t take long to read it.

Time for reflection

Many people have taken great encouragement from reading Mark’s good-news story. Written originally for Christian believers in Rome, it has travelled through time and across the world. The good news about Jesus has transformed lives and intrigued people.

So, what about our good-news stories? Can they have an effect on others?

First, I think that we should answer that question by considering the general news that we take in. So much of what we hear or see on TV, radio, websites and social media is not good news. In fact, it’s generally bad news.

Bad news needs the antidote of good news. To save us from sinking into depression, and feeling that the world is deteriorating, we need the opposite, to create a balance. We need to believe that there is hope, there is possibility, there is a reason to get up tomorrow. So, our good-news story may be the one that encourages someone else. Maybe we’ll be glad of their good-news story at some point in the future when it’s us who are feeling down.

So, let’s share and celebrate good news!